School of Health Student Uncovers the Impact of Ecological Changes on Indigenous Peoples’ Mental Health

Top Image: A scene from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, where Arjun Chhabra (H’25, M’29) conducted research into connections between mental health among the Oglala Lakota people and changing environmental conditions.

(May 28, 2025) — While members of the Oglala Lakota people expressed feelings of grief, fear and concern when asked about changing environmental conditions and mental health, they also shared a strong resilience and commitment to adapting, Arjun Chhabra (H’25, M’29) found during interviews on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge reservation he conducted in the summer of 2024.

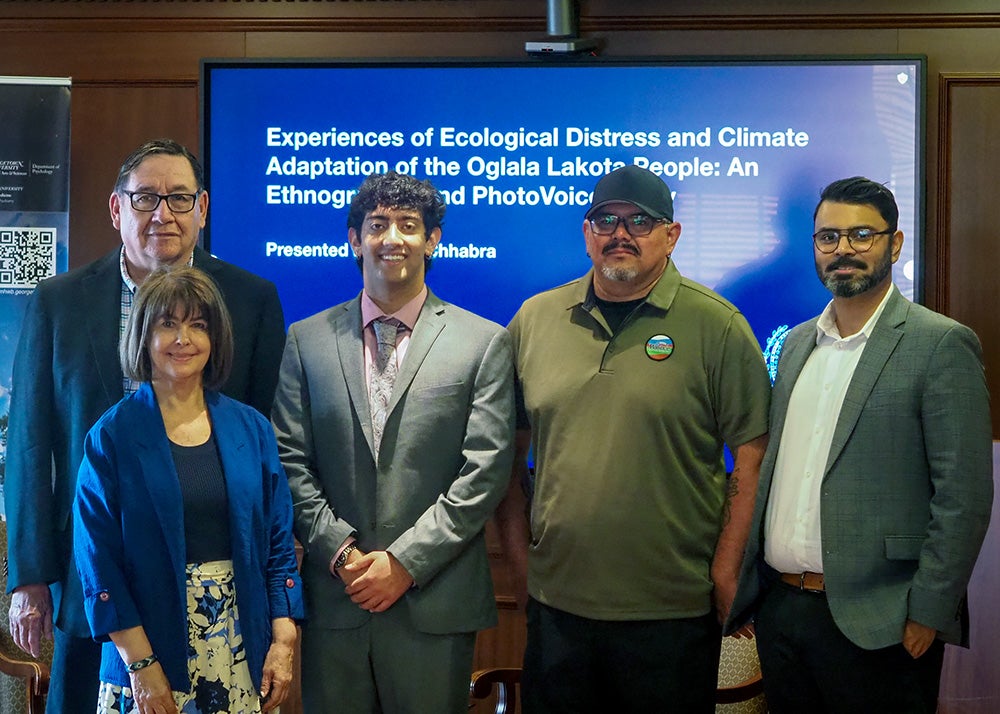

Arjun Chhabra (H’25, M’29) presented his research during an April event at the Mortara Center for International Studies.

“The Oglala Lakota people nearly always accompanied feelings of climate resilience along with awareness of ecological distress,” said Chhabra. “Lakota people often refer to their tribal history where they learned to adapt and survive.”

Many Oglala Lakota people still live on their ancestral land, which creates a feeling of the need to protect and preserve the land for future generations, according to Chhabra. “Homeland is still very important to the Oglala Lakota people,” he said. “It represents tribal members’ strong connection to their culture.”

Well-Prepared for Field Research

Chhabra (H’25) was drawn to Georgetown for the School of Health, especially the global health major.

“I took a course in high school on population health and became interested more in global health and thought Georgetown, located in Washington, D.C., had the most opportunities to be engaged with the most relevant and pressing topics,” said Chhabra. Looking back, Chhabra credits his professors for bringing their real world knowledge into the classroom and connecting his coursework to actions on Capitol Hill.

Chhabra lived in rural western Australia the fall of his senior year

Chhabra also believes his School of Health classes and his experiential learning opportunities set him up well for his field research.

During the fall of his senior year, Chhabra lived in rural western Australia as part of the global health experiential learning program, where he worked with a rural health organization on a qualitative study. The study involved interviews with local nurses and dietitians to understand why there were low rates of credentialing to become a diabetes educator despite the fact that diabetes was a major health concern for the region.

“Being in that small town in western Australia, I experienced firsthand the importance of listening to and learning from experts about challenges in the area,” said Chhabra. “The qualitative study highlighted the perspectives of local health practitioners, as interview participants explained the roadblocks surrounding diabetes educator credentialing, such as the difficulty in gaining the clinical hours necessary for the certification because the rural population is so small.”

A Growing Interest in Indigenous Health

Chhabra knew during his sophomore year he wanted to pursue research related to population health. He grew interested in the connection between the environment and mental health, and met with Shabab Wahid, PhD, assistant professor in the department of global health. Wahid has written about adverse mental health outcomes for people in Bangladesh related to climate-related stressors. Chhabra wanted to build on this research by investigating how indigenous people in the United States are impacted by environmental changes.

Chhabra with Shabab Wahid, PhD

With the assistance of Bette R. Jacobs, PhD, professor of health systems administration, Chhabra contacted Tally Plume, who would eventually become Chhabra’s host on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Plume agreed to let him live on the reservation and the tribal review board approved Chhabra to interview tribal members about how changes in the environment impacted their mental health.

“I used the snowball method for recruiting participants, where the last person I interviewed made a recommendation on who I could speak with next,” said Chhabra, who was able to conduct 17 interviews in total. Chhabra also used PhotoVoice, a participatory action research method that involved having tribal members send photos of their surrounding environment and then asking them questions about the photos related to climate change impacts.

“The PhotoVoice method allowed people to highlight why the image is important and how it represents the impact of environmental changes, in their own words,” said Chhabra. He also displayed several of the images from tribal members when he presented his research at Georgetown at the end of April. Wanting to foreground the words of the Oglala Lakota people, Chhabra also invited two members of the tribe to speak at the research presentation.

(From l) Tally Plume, Bette R. Jacobs, PhD, Chhabra, Nick Hernandez and Shabab Wahid, PhD

One of the Oglala Lakota speakers, Nick Hernandez, owns an agricultural development business on the reservation, where he focuses on growing native ecology. Plume also provided the event audience with background on the Pine Ridge Reservation and the Oglala Lakota people, as well as a local perspective on environmental changes.

Future Practice

Chhabra believes he walked away from his time on the reservation a changed person, especially in how he thinks about caring for people as a future physician.

“This research made me reflect on what caring for the whole person means, in thinking about not only the physical effects a person may be experiencing, but also their mental health,” said Chhabra.

An incoming student at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, Chhabra was admitted through the early assurance program (EAP). He hopes to apply what he has learned about supporting vulnerable populations to future research and practice.

Both his time on the reservation and the time he spent in the experiential learning course in rural Australia provided Chhabra with an appreciation for providers practicing health care in rural settings.

“I hope to bring these experiences in providing patient care, understanding the determinants that influence someone’s health, such as the environment, socioeconomic status and access, to health care,” said Chhabra.

Heather Wilpone-Welborn

GUMC Communications